Retracing History

The Enslaved.org database—led by MSU researchers—encompasses more than 5 million data points about enslaved people, people who owned slaves, and others who participated in the historical slave trade.

Retracing History

The Enslaved.org database—led by MSU researchers—encompasses more than 5 million data points about enslaved people, people who owned slaves, and others who participated in the historical slave trade.

June 22, 2021Imagine not knowing who your ancestors were, what they were like, what they did and how their path eventually led to yours.

For those who are the descendants of enslaved people, this is frustratingly common.

Up until now, large chapters of their family histories, their genealogy, even the stories about what their ancestors’ lives may have been like, have been buried. By poor record-keeping, by inconsistent academic interest or, worst of all, by a revisionist version of history that implies that their lives weren’t worth documenting in a truthful way at all.

“One of the problems with the history of slavery is often that people say, ‘We can’t know anything about the slaves—they’re lost to history.’ But that’s simply not true,” says Dean Rehberger, associate professor of history and director of the MATRIX center at MSU. “The sad fact is, because they were treated as property, there’s often more records. If we can bring all of this data together—tiny little fragments of a person’s life—and sew it together, we can actually start to recreate lives.”

Rehberger is co-principal investigator on a project here at Michigan State that is doing just that—and ensuring that erasure of the people and events of the historical slave trade won’t continue. “Records about enslaved people are decaying and disappearing,” says Walter Hawthorne, MSU’s other co-principal investigator and a professor of African history. “The time to extract information from them and make them widely accessible to scholars and members of the public is now.”

Enslaved: Peoples of the Historical Slave Trade (Enslaved.org for short) is a one-of-a-kind hub that is bringing together data collections from multiple universities, archives, museums and family history centers to help deepen the understanding, dignity and respect of the millions of people who were victim to the centuries-long slave trade.

Enslaved.org makes records freely available and fully searchable. It is an ever-growing project that currently encompasses 5 million data points about more than 600,000 people, including individuals who were enslaved, those who owned slaves, those who were connected to the slave trade and those who worked to emancipate enslaved people.

Recently, Enslaved.org entered a new phase of data collection: crowdsourcing. By welcoming contributions from the public—especially descendant communities—as well as academic contributions from researchers outside the project’s original workgroup, the database will only grow richer and more comprehensive.

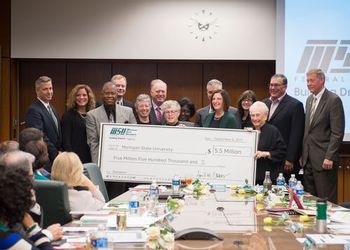

An initial $99,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities helped launch the project in its earliest iteration in 2011, and more than $3.7 million from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation—including a recent $1.4 million grant, which Michigan State received this March—has helped shape Enslaved.org into what it is today.

Why Michigan State?

Michigan State has one of the top-ranked African history graduate programs in the nation (U.S. News & World Report).

Michigan State also has MATRIX, one of the country’s premier digital humanities centers, which specializes in building and optimizing technical infrastructures to house collections of cultural and historical materials. MATRIX has worked with museums, libraries, archives and world heritage sites, and places special emphasis on its work with African scholars and institutions.

A variety of perspectives, methods and resources from collaborators at the University of Maryland’s College of Arts and Humanities, the Data Semantics Lab at Kansas State University and the Harvard University Hutchins Center for African and African American Research are also playing a critical role in the project.

Who benefits from this effort?

The general public: who can read stories and detailed biographical information about named individuals, as well as find genealogical information about those who were enslaved, owned slaves or participated in the historical slave trade.

K–12 educators: who can find more robust teaching materials about the slave trade and the lives of enslaved people than those that appear in most K–12 textbooks.

Scholars: who can analyze and download information about enslaved people, enslavers and others associated with enslavement and liberation on three continents, and who can publish peer-reviewed datasets and data articles through the project.

How can philanthropy help?

Enslaved is currently seeking funding for the following priorities:

- Endowed positions that will help recruit dedicated researchers specifically for the project

- Undergraduate research opportunities

- Graduate research opportunities

- Development of a dedicated K–12 component that includes lesson plans and materials for teachers

- Funding to add more people records and develop the project’s functionality

LEARN MORE about supporting the project by contacting College of Social Science Senior Director of Development Alexandra Tripp at actripp@msu.edu or by calling (517) 884-2189.

Header artwork: “Market Stall and Market Women, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1819–1820,” Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed June 2021, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/725