Synergy, Ignited

Endowed faculty positions are putting top teachers, physicians and researchers in the right place, at the right time, to move MSU forward.

Synergy, Ignited

Endowed faculty positions are putting top teachers, physicians and researchers in the right place, at the right time, to move MSU forward.

October 27, 2020For MSU’s endowed faculty, being able to make the most of an opportunity is far more than a happy coincidence. The positioning of an academic all-star, the marshalling of resources—all are part of a well-thought-out plan, years in the making. It starts with the vision of donors whose passion and generosity create an endowed position. Add in the aspirations of a teacher, physician or researcher who is named to hold the position. And finally, top it off with an unwavering commitment to genuinely partner with communities of people whose lives, in turn, will be forever changed because of the work that endowed positions fund. It’s synergy, on fire.

![]()

The C.S. Mott Professorships in MSU’s Public Health Division in Flint are a perfect example of how the effect of endowed positions can quickly multiply. A $9 million endowment from the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation in 2014 now funds four professors and has made the College of Human Medicine’s Flint campus an epicenter for work in the field of public health.

“With the steep challenges we currently face, and through the foundation’s investment, we are now uniquely positioned to reduce health disparities and create equity through education and research,” says Interim Dean Aron Sousa.

Letting the community guide decisions…from the start

The Division of Public Health in downtown Flint, now comprising 16 faculty members, is one of the fastest-growing research divisions at MSU, bringing in more than $72 million in grants to the community, including the Flint Lead Exposure Registry. Its leaders are steeped in the community.

When Debra Furr-Holden, a trailblazing epidemiologist from Johns Hopkins University who wanted to make a difference, first accepted a C.S. Mott Professorship in Flint five years ago, she knew exactly where she was going and why. She had spent her teen years in Flint and she was excited by the groundwork that had already been laid there for a truly community-engaged public health program. Now associate dean for Public Health Integration, she says she wanted to be not just a professor but a scholar activist making a difference that could be “seen, touched and felt.”

“I’ve had the opportunity to contribute and bring my gifts, talents and training to bear at a time and in a place where the need was great, but also the will of the people was just out of this world,” she says. “The Mott Foundation and the people of Flint gave me a big opportunity to stand true to who I say I am.”

Working with her is C.S. Mott Professor Mona Hanna-Attisha, the renowned pediatrician and public health advocate whose research first exposed the Flint water crisis. Hanna-Attisha says she first fell in love with Flint, pediatrics and the community-based, community-service approach of MSU’s College of Human Medicine as a medical student. Later, when she had just completed her master’s in public health, she began hearing about the Mott Foundation’s support for building a new kind of public health model in Flint. Like Furr-Holden, she jumped at an opportunity to return, in her case to lead an MSU pediatrics residency program in 2011.

“There was this commitment to build public health capacity in Flint in a way that had never been done before,” she says, “to work in total partnership with the community to identify needs, and then build capacity with the community to improve disparities.”

She couldn’t have known how much of an impact her dedication to this work would have in Flint, but the work continues to inspire her.

“We are here because we want to make an actionable, demonstrated difference in the lives of the community that we are privileged to work with,” she says. “We know our work isn’t just about research that’s going to be in a publication, but that what we are doing in Flint is actually improving the lives of people.”

A base of support fosters rapid growth

The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation recognized a need to address a myriad of challenges facing the Flint area through a public health lens, says Neal Hegarty, vice president of programs. The foundation also saw MSU’s commitment to a community-based approach, he says, where meaningful engagement with residents is one of the most important metrics and working to address issues that are identified by the community is a core strategy. A shared appreciation for practical approaches that directly help the people of Flint is deeply embedded in the partnership.

“Both MSU and the Mott Foundation value community impact, and we both recognize the strength that exists in all aspects of our community,” he says. “MSU public health is committed to all voices, especially the most underserved in society.”

This puts Flint and MSU’s public health program on the leading edge for finding solutions to health disparities. When Governor Gretchen Whitmer recently declared racism as a public health crisis in Michigan, such a declaration had already happened in Flint, which is poised to become a model for the rest of the state in how environmental injustice can be addressed.

The public health program has grown, evolved and expanded exponentially beyond the foundation’s initial investment, notes Hegarty.

The foundation, the professors, the university and the community have set a virtuous cycle in motion, with each spin helping to build up strengths that in turn build up other strengths. While the program was designed and implemented before the Flint water crisis, it was in place and ready to act to support the people of Flint at a critical time, as it is now during the COVID-19 pandemic.

For example, the National Institutes of Health recently funded a study led by C.S. Mott Professor Todd Lucas with a pair of formidable goals: communicating effectively about the value of COVID-19 antibody testing and better understanding why COVID-19 causes a disproportionate number of African Americans to suffer severe cases and deaths.

“Rather than rest on laurels, the entire team has worked aggressively to grow, evolve and develop with the endowed funds as core resources,” Hegarty says. “To me, this work represents some of the best community-engaged scholarship, and the first few years of work has set a base for many years of impact for the Flint community.”

All the C.S. Mott professors see the foundation’s support as vital to their success.

Senior clinical psychologist Jennifer Johnson left a large, Ivy League psychiatry department to come to an empty building in Flint to begin MSU’s Division of Public Health as the first Mott Professor. It was a risk she was willing to take to have the opportunity to help build something new and build it right.

“I had never seen a university build an academic unit in partnership with a community,” she says. “I knew if I was serious about making a difference, I had to come here, as the very first person, ensuring that the division was built on a foundation of academic excellence and stayed true to its community-partnered mission.”

Her research is aimed at improving the mental health and substance abuse care for pregnant women and people involved in the criminal justice system. She has been extremely successful in Flint, as evidenced by a prolific number of grants and publications.

Her portfolio of work includes many firsts; the first large randomized trial of any treatment for major depressive disorder in an incarcerated population; the first randomized trial of suicide prevention for justice-involved individuals; and an extensive study of the scale-up of a postpartum depression prevention program in 90 prenatal clinics serving low-income women nationally.

“The endowed professorships allow us to take more risks and to pursue bigger efforts to make the large, systemic changes that are needed to improve health for vulnerable populations,” she says. “They also provide us with prominence and stature to bring attention to needed issues, system reforms and invisible populations.”

A health psychologist, Lucas is the newest Mott Professor. His research is aimed at developing effective interventions to change stress experiences and promote health behaviors like screening tests as a means to address health disparities, especially in minority populations. For him, the Mott Professorship is a “dream come true.”

“It provides support to effect great change in areas that I am directly interested in, and also a higher purpose in connecting this change to the Flint community,” he says. “Great things happen when big ideas are supported, and that’s where I feel I am at.”

Furr-Holden likens it to being empowered to swing wide and swing hard.

“Having that endowment allows us to be bold,” she says, “to do the kind of innovative, collaborative, community-partnered research that would otherwise be difficult. We get to say ‘let’s go, game on.’”

A tool to recruit the very best

Endowed chairs date at least as far back as ancient Rome. Steeped in tradition and ceremony, they represent the highest accolade a university can bestow upon a professor. Endowed positions send a strong message about what is valued at the university, which in turn attracts people who want to innovate in those areas.

So important are chairs that recruiting a world-class faculty member sometimes cannot happen without them, according to Sousa, who has played a key role in filling critical faculty positions to expand the college’s research and service mission. He notes that it can take more than a year to fill specific gaps with the right faculty, as those with the highest level of accomplishment typically have deep roots in the academic community, including extensive research teams and labs. It can take time and convincing for them to make a transition.

“We know these positions act as a magnet—attracting highly talented faculty and making it clear that the MSU College of Human Medicine has opportunities and resources to offer nationally renowned faculty,” he says. “These funds open doors and allow the college to impact public health on a large scale—with opportunities we would not otherwise have.”

Endowed positions allow colleges and departments to go into the recruitment process with confidence.

![]()

Re-engineering engineering…creatively

When Thomas Wielenga approached MSU in 2017 with the intention of making a gift to support the College of Engineering, he had some very specific ideas in mind.

Wielenga—who earned his undergraduate degree in 1978 and went on to pursue a master’s degree in computer-aided design and a Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from University of Michigan—wanted to establish an endowed professorship in mechanical engineering. He wanted MSU to use the position as a lure for someone who wasn’t just a great researcher, but also an innovative teacher with big ideas on how to improve engineering education as a whole. And he wanted to call it the Wielenga Creative Engineering Endowed Professorship.

This idea stemmed from Thomas’s abiding belief that creativity is essential to everything.

“My philosophy is that there’s something called the creative process, and that everything evolves through that process,” he says. “It’s how we became humans and how humans invented things and the processes by which we use the things.”

A professor of mechanical engineering who was willing to be that creative force was exactly what Michigan State needed, he thought. He could not possibly have foreseen just how valuable that creativity would be in 2020.

Teaching teachers how to teach in a time of COVID-19

Michele Grimm, the inaugural Wielenga Creative Engineering Endowed Professor, had just finished teaching her morning classes on March 11, 2020, when it was announced that students should immediately return home to complete their semesters remotely. For Grimm, the transition to teaching in a virtual format felt seamless. Her regular course materials relied heavily on technology and digital experiences, so she could continue her lessons as planned, with minimal interruption to her students’ learning.

But for many of her colleagues in the College of Engineering, it wasn’t so easy, and concern about the 2020-2021 school year loomed. So, Grimm offered herself up as a resource, headed up a committee and spent the summer helping as many engineering faculty members as possible get ready for a fall semester unlike any other.

She says: “Rather than trying to exactly replicate what we’ve always done in person into an online environment, I encouraged everybody to take a step back and look at the objectives—what do we want students to get out of these lessons, and how can we get there without hands-on, in-person instruction?”

With more than two decades of research and experience in the world of curriculum development—and a deep appreciation for the value of working in virtual spaces from a research perspective—this was a challenge that Grimm was completely prepared to tackle.

Taking the title of “teacher” — and running with it

At the outset, Michele Grimm’s teaching career was only supposed to last three years. At least, that’s what she told herself in 1994, when her husband’s medical residency landed the pair in Detroit and she was offered a three-year position at Wayne State.

In the 25 years that followed, she not only taught courses, she helped design them. She developed Wayne State’s undergraduate and graduate programs in biomedical engineering, served as associate dean for seven years, and found that she loved the administrative side of academia just as much as the research side.

Much of her work at Wayne State focused on developing engineering curriculum that used technology and hands-on experiences in new ways, and was more engaging than traditional lecture-style instruction.

Outside of her work on the administrative side, Grimm’s research walks the line between engineering and medicine in the field of injury biomechanics, in particular, neonatal brachial plexus injuries. Due to the nature of these injuries—they are rare and occur as a result of the way a baby’s body passes through the birth canal—it is not possible to conduct patient-based clinical studies. So recreating the circumstances virtually helps engineers and doctors work together to figure out exactly how they happen and how to prevent them.

The body of scientific research she built at Wayne State will continue to play a big part in her career here at Michigan State, but digging into how to make engineering education click with students is what made her truly excited to bring her talents to East Lansing.

“I always said I wasn’t going to leave Wayne State for ‘just another faculty position,’” Grimm says. “I was actually considering department chair positions when the Wielenga Professorship at Michigan State came available. It was clear that in this position, I’d be able to do some really neat things—work with the department and come up with creative solutions—without the administrative burden hanging over me.”

Future-proofing higher education

The work Grimm is doing will help the College of Engineering do two things that Thomas Wielenga believes are imperative: first, make an engineering degree more cost-effective by both reducing time to graduation and graduating students who are more immediately prepared for the workforce; second, help a brick-and-mortar university like MSU keep up with online degree programs that are only going to become more popular.

“I felt that the way engineering is taught now is very similar to the way I learned it 40 years ago. Even the textbooks are nearly the same. But there is a whole new set of tools that exist now. I wanted Michigan State to be able to bring in someone with a creative approach to using those tools,” says Wielenga.

Conversations between Grimm and Wielenga have sparked plenty of interesting concepts to try, one of which involves using a computer environment to turn real-life problems into a game—a virtual choose-your-own-adventure lab.

“We need to make sure that students who are graduating as engineers actually know how to do engineering,” Dr. Grimm says. “The theory behind engineering is important, but entering the workforce having had experience actually doing the engineering is just as—if not more—important.”

In a time when “going out into the world” is not encouraged, being able to replicate hands-on learning experiences in a virtual setting is more important than ever.

This is exactly the kind of creativity Thomas Wielenga had in mind, though he swears he does not have a crystal ball. He just knows that the world is going to keep creating new challenges, and universities have no choice but to keep creating solutions to meet them.

![]()

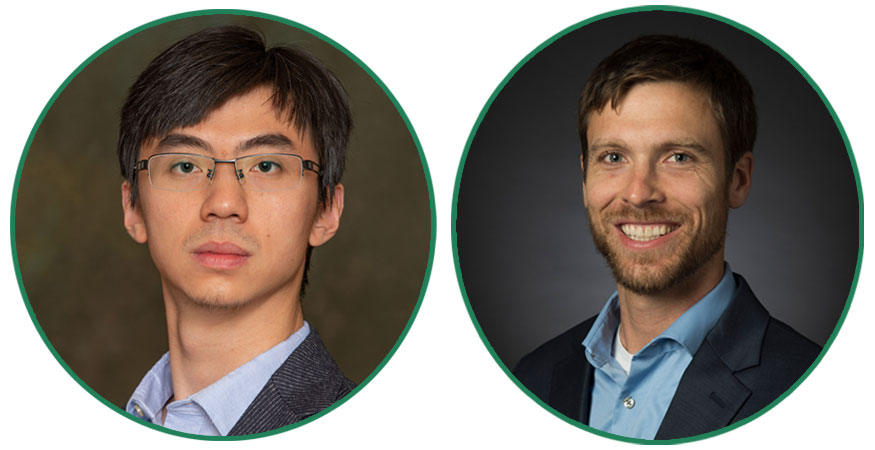

Welcoming new faces, and lifting up familiar ones

It is common to talk about endowed faculty positions as recruiting tools to lure highly accomplished teachers and researchers to MSU from other institutions. But an endowed position is also an excellent way for Michigan State to acknowledge and add fuel to the great work that its existing faculty members have been doing on campus for years.

It is common to talk about endowed faculty positions as recruiting tools to lure highly accomplished teachers and researchers to MSU from other institutions. But an endowed position is also an excellent way for Michigan State to acknowledge and add fuel to the great work that its existing faculty members have been doing on campus for years.

The College of Engineering did this recently with Xiaobo Tan, naming him the prestigious Richard M. Hong Endowed Chair in Electrical Engineering.

Tan joined MSU in 2004, and has been steadily earning accolades and building his body of research ever since. He earned an NSF CAREER award in 2006, an MSU Teacher-Scholar Award in 2010, and was named an MSU Foundation Professor in 2016. In 2018, he received the College of Engineering’s Withrow Distinguished Scholar Award. He has published more than 250 peer-reviewed papers and holds four U.S. patents in his research areas.

An endowed position will only add to his impressive list of accomplishments—and it will uplift Tan’s entire area of research, too.

“I look forward to working with my colleagues within the department and beyond to advance our education and research goals. In particular, I plan to use the funds to help propel MSU’s excellence in robotics.”

![]()

Opportunities to grow their field. . . and grow IN their field

In 2011, an anonymous alumnus of the MSU College of Natural Science made a $7 million gift to help expand the college’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences (EES). Included in the gift was funding for endowed faculty positions specifically intended for early career faculty members.

These positions helped MSU attract Songqiao “Shawn” Wei and Dalton Hardisty—both fresh off their Ph.D.s and postdocs, and ready to breathe new life into the area of earth science at MSU—and gave them use of the funding and prestige of their endowed positions to unlock their potential as teachers, researchers and future leaders in their respective fields.

Wei, an Endowed Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences, is a seismologist whose star is already on the rise.

It was just announced in September that Wei and his team secured a $1.1 million National Science Foundation grant—which also provides an additional $4.1 million worth of ship time and instrument usage for two seagoing expeditions—to study the Earth’s mantle in the Tonga-Lau-Samoa region of the Pacific Ocean.

Wei is the lead principal investigator for the project, which, he says, took a great deal of persistence to get funded. Though he has been studying the Tonga-Lau-Samoa subduction zone for more than 10 years, he has never actually been to the site, and he has a certain youthful excitement about it.

“That subduction zone has been my main focus, so I really want to go there,” Wei said. “It is where plate tectonics and subduction were discovered by scientists in the 1960s. Before that, there was no clue of plate tectonics. To me, this is kind of a historic place, and very exciting.”

Dalton Hardisty completed his Ph.D. in oceanography at University of California, Riverside, and his post-doc at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute before joining Michigan State and being named an Endowed Assistant Professor of Geological Sciences.

Hardisty is an expert in the areas of paleoceanography and geochemistry and leads a team that is studying the history of ocean and atmosphere chemistry. He, too, is a recent recipient of a $1 million National Science Foundation grant, from its Division of Ocean Sciences, to investigate the impact of ever-expanding low-oxygen zones in the ocean.

At his college Investiture lecture in the spring of 2019, he spoke about how it feels to hold an endowed professorship.

“I am particularly proud and feel a sense of responsibility to have one of these endowed positions, and I take it very seriously,” he said. “I am looking forward to being a leader in the department, and helping the department maintain its status as a leader going forward.”

Dave Hyndman, professor and EES department chair, said that he is very proud of the accomplishments of Drs. Wei and Hardisty.

“They are exemplars of all the things we look for when we hire new faculty members—exceptional creativity, a hardworking spirit and team players, Hyndman says. “Their early career successes have helped them to become leaders in their fields. The endowed gift from our generous alumni was critical to hiring such outstanding scientists to our departmental team, which has been a key to our continued success as a unit.”

LEARN MORE about support for endowed faculty positions by contacting the development officer in your college or unit or by calling (517) 884-1000.

VISIT MSU’s official Honored Faculty website, where you can search and sort by name, college or position to learn more about some of MSU’s best and brightest faculty members at msu.edu/honoredfaculty